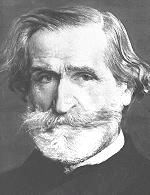

(born

Roncole, 9/10 October 1813; died Milan, 27 January 1901).

(born

Roncole, 9/10 October 1813; died Milan, 27 January 1901).

He was born into a family of small landowners and taverners. When he was seven he was helping the local church organist; at 12 he was studying with the organist at the main church in nearby Busseto, whose assistant he became in 1829. He already had several compositions to his credit. In 1832 he was sent to Milan, but was refused a place at the conservatory and studied with Vincenzo Lavigna, composer and former La Scala musician. He might have taken a post as organist at Monza in 1835, but returned to Busseto where he was passed over as maestro di cappella but became town music master in 1836 and married Margherita Barezzi, his patron's daughter (their two children died in infancy).

Verdi had begun an opera, and tried to arrange a performance in Parma or Milan; he was unsuccessful but had some songs published and decided to settle in Milan in 1839 where his Oberto was accepted at La Scala and further operas commissioned. It was well received but his next, Un giorno di regno, failed totally; and his wife died during its composition. Verdi nearly gave up, but was fired by the libretto of Nabucco and in 1842 saw its successful production, which carried his reputation across Italy, Europe and the New World over the next five years. It was followed by another opera also with marked political overtones, I lombardi alla prima crociata, again well received. Verdi's gift for stirring melody and tragic and heroic situations struck a chord in an Italy struggling for freedom and unity, causes with which he was sympathetic; but much opera of this period has political themes and the involvement of Verdi's operas in politics is easily exaggerated.

The period Verdi later called his 'years in the galleys' now began, with a long and demanding series of operas to compose and (usually) direct, in the main Italian centres and abroad: they include Ernani, Macbeth, Luisa Miller and eight others in 1844-50, in Paris and London as well as Rome, Milan, Naples, Venice, Florence and Trieste (with a pause in 1846 when his health gave way). Features of these works include strong, sombre stories, a vigorous, almost crude orchestral style that gradually grew fuller and richer, forceful vocal writing including broad lines in 9/8 and 12/8 metre and above all a seriousness in his determination to convey the full force of the drama. His models included late Rossini, Mercadante and Donizetti. He took great care over the choice of topics and about the detailed planning of his librettos. He established his basic vocal types early, in Ernani the vigorous, determined baritone, the ardent, courageous but sometimes despairing tenor, the severe bass; among the women there is more variation.

The 'galley years' have their climax in the three great, popular operas of 1851-3. First among them is Rigoletto, produced in Venice (after trouble with the censors, a recurring theme in Verdi) and a huge success, as its richly varied and unprecedentedly dramatic music amply justifies. No less successful, in Rome, was the more direct Il trovatore, at the beginning of 1853; but six weeks later La traviata, the most personal and intimate of Verdi's operas, was a failure in Venice - though with some revisions it was favourably received the following year at a different Venetian theatre. With the dark drama of the one, the heroics of the second and the grace and pathos of the third, Verdi had shown how extraordinarily wide was his expressive range.

Later in 1853 he went - with Giuseppina Strepponi, the soprano with whom he had been living for several years, and whom he was to marry in 1859 - to Paris, to prepare Les vêpres siciliennes for the Opéra, where it was given in 1855 with modest success. Verdi remained there for a time to defend his rights in face of the piracies of the Théâtre des Italiens and to deal with translations of some of his operas. The next new one was the sombre Simon Boccanegra, a drama about love and politics in medieval Genoa, given in Venice. Plans for Un ballo in maschera, about the assassination of a Swedish king, in Naples were called off because of the censors and it was given instead in Rome (1859). Verdi was involved himself in political activity at this time, as representative of Busseto (where he lived) in the provincial parliament; later, pressed by Cavour, he was elected to the national parliament, and ultimately he was a senator. In 1862 La forza del destino had its premiere at St. Petersburg. A revised Macbeth was given in Paris in 1865, but his most important work for the French capital was Don Carlos, a grand opera after Schiller in which personal dramas of love, comradeship and liberty are set against the persecutions of the Inquisition and the Spanish monarchy. It was given in 1867 and several times revised for later, Italian revivals.

Verdi returned to Italy, to live at Genoa. In 1870 he began work on Aida, given at Cairo Opera House at the end of 1871 to mark the opening of the Suez Canal (Verdi was not present): again in the grand opera tradition, and more taut in structure than Don Carlos. Verdi was ready to give up opera; his works of 1873 are a string quartet and the vivid, appealing Requiem in honour of the poet Manzoni, given in 1874-5, in Milan (San Marco and La Scala, aptly), Paris, London and Vienna. In 1879 the composer-poet Boito and the publisher Ricordi prevailed upon Verdi to write another opera, Otello; Verdi, working slowly and much occupied with revisions of earlier operas, completed it only in 1886. This, his most powerful tragic work, a study in evil and jealousy, had its premiere in Milan in 1887; it is notable for the increasing richness of allusive detail in the orchestral writing and the approach to a more continuous musical texture, though Verdi, with his faith in the expressive force of the human voice, did not abandon the 'set piece' (aria, duet etc) even if he integrated it more fully into its context - above all in his next opera. This was another Shakespeare work, Falstaff, on which he embarked two years later - his first comedy since the beginning of his career, with a score whose wit and lightness betray the hand of a serene master, was given in 1893. That was his last opera; still to come was a set of Quattro pezzi sacri (although Verdi was a non-believer). He spent his last years in Milan, rich, authoritarian but charitable, much visited, revered and honoured. He died at the beginning of 1901; 28,000 people lined the streets for his funeral.