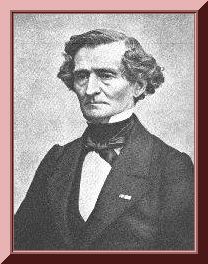

(born

La Côte-St-André, Isère, 11 December 1803; died Paris,

8 March 1869).

(born

La Côte-St-André, Isère, 11 December 1803; died Paris,

8 March 1869).

As a boy he learned the flute, guitar and, from treatises alone, harmony (he never studied the piano); his first compositions were "romances" and small chamber pieces. After two unhappy years as a medical student in Paris (1821-3) he abandoned the career chosen for him by his father and turned decisively to music, attending Le Sueur's composition class at the Conservatoire. He entered for the Prix de Rome four times (1827-30) and finally won. Among the most powerful influences on him were Shakespeare, whose plays were to inspire three major works, and the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he idolized, pursued and, after a bizarre courtship, eventually married (1833). Beethoven's symphonies too made a strong impact, along with Goethe's "Faust" and the works of Moore, Scott and Byron. The most important product of this time was his startlingly original, five movement "Symphonie fantastique" (1830).

Berlioz's 15 months in Italy (1831-2) were significant more for his absorption of warmth, vivacity and local colour than for the official works he wrote there: he moved out of Rome as often as possible and worked on a sequel to the "Symphonie fantastique" ("Le retour à la vie", renamed "Lélio" in 1855) and overtures to "King Lear" and "Rob Roy", returning to Paris early to promote his music. Although the 1830s and early 1840s saw a flow of major compositions - "Harold en Italie", "Benvenuto Cellini", "Grande messe des morts", "Roméo et Juliette", "Grande symphonie funebre et triomphale", "Les nuits d'été" - his musical career was now essentially a tragic one. He failed to win much recognition, his works were considered eccentric or 'incorrect' and he had reluctantly to rely on journalism for a living; from 1834 he wrote chiefly for the "Gazette musicale" and the "]ournal des débats".

As the discouragements of Paris increased, however, performances and recognition abroad beckoned: between 1842 and 1863 Berlioz spent most of his time touring, in Germany, Austria, Russia, England and elsewhere. Hailed as an advanced composer, he also became known as a leading modern conductor. He produced literary works (notably the "Mémoires") and another series of musical masterpieces - "La damnation de Faust", the "Te Deum", "L'enfance du Christ", the vast epic "Les troyens" (1856-8; partly performed, 1863) and "Béatrice et Bénédict" (1860-62) - meanwhile enjoying happy if short-lived relationships with Liszt and Wagner. The loss of his father, his son Louis (1834-67), two wives, two sisters and friends merely accentuated the weary decline of his last years, marked by his spiritual isolation from Parisian taste and the new music of Germany alike.

A lofty idealist with a leaping imagination, Berlioz was subject to violent emotional changes from enthusiasm to misery; only his sharp wit saved him from morbid self-pity over the disappointments in his private and professional life. The intensity of the personality is inextricably woven into the music: all his works reflect something in himself expressed through poetry, literature, religion or drama. Sincere expression is the key - matching means to expressive ends, often to the point of mixing forms and media, ignoring pre-set schemes. In "Les troyens", his grand opera on Virgil's "Aeneid", for example, aspects of the monumental and the intimate, the symphonic and the operatic, the decorative and the solemn converge. Similarly his symphonies, from the explicitly dramatic "Symphonie fantastique" with its "idée fixe" (the theme representing his beloved, changed and distorted in line with the work's scenario), to the picturesque "Harold en Italie" with its concerto element, to the operatic choral symphonic tone poem "Roméo et Juliette", are all characteristic in their mixture of genres. Of his other orchestral works, the overture "Le carnaval romain" stands out as one of the most extrovert and brilliant. Among the choral works, "Faust" and "L'enfance du Christ" combine dramatic action and philosophic reflection, while the "Requiem" and "Te Deum" exploit to the full Berlioz's most spacious, ceremonial style.

Though Berlioz's compositional style has long been considered idiosyncratic, it can be seen to rely on an abundance of both technique and inspiration. Typical are expansive melodies of irregular phrase length, sometimes with a slight chromatic inflection, and expressive though not tonally adventurous harmonies. Freely contrapuntal textures predominate, used to a variety of fine effects including superimposition of separate themes; a striking boldness in rhythmic articulation gives the music much of its vitality. Berlioz left perhaps his most indelible mark as an orchestrator, finding innumerable and subtle ways to combine and contrast instruments (both on stage and off), effectively emancipating the procedure of orchestration for generations of later composers. As a critic he admired above all Gluck and Beethoven, expressed doubt about Wagner and fought endlessly against the second-rate.

Berlioz wrote the first important treatise on orchestration, "Traité d'instrumentation et orchestration modernes," published in Paris in 1844. A modern edition was published in New York in 1948. In addition, Berlioz frequently contributed critical essays to the "Gazette Musicale," and he published a book of essays on orchestral music, "Les Soirées de l'orchestre," Paris, 1853 ("Evenings in the Orchestra, 1956).